The Market for Female Surrealists Has Finally Reached a Tipping Point

The Market for Female Surrealists Has Finally Reached a Tipping Point

Tess Thackara Sep 26, 2018 5:00 pm

In 2009, Leonora Carrington first cleared $1 million at auction with her painting The Giantess (1947). An image of a cloaked queen hovering, leviathan-like, over a mystical, abundant landscape, it was, according to Christie’s specialist Virgilio Garza, “one of the most beautiful things” he’d ever handled.

Carrington, who was fiercely independent and, according to her longtime gallerist Wendi Norris, cared primarily about critical and curatorial recognition, passed away in 2011 at the age of 94. Were she still alive today, it might bring her greater pleasure to know that over the past five years, institutional interest in her work has risen considerably, helping to double and triple that $1 million milestone. She is not alone; rather, she is one of a number of female artists affiliated with the Surrealist movement—including Dorothea Tanning, Remedios Varo, Kay Sage, and Leonor Fini—who have seen a recent acceleration of interest from curators, academics, and collectors.

Leonora Carrington, The Dark Night of Aranoë, 1976. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Leonora Carrington, The Giantess (The Guardian of the Egg), 1942. Courtesy of Christie’s.

At a moment of reckoning with male power, the prescient work of these artists is resonating with wider audiences, in what Whitney Chadwick, author of the 1985 Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement, attributes in part to “an opening up of cultural feeling” about female sexuality.

“These female painters challenged sexual and gender boundaries from a very early time,” said Chadwick, who, last year, published Farewell to the Muse: Love, War and the Women of Surrealism, a book that traces some of the influential friendships that flourished between the women. “Now the Surrealist women are being cultivated as serious and significant artists.”

It’s a development that goes hand in hand with the continuing appetite for historical, underrecognized female artists, and is accompanied by a broader renewed interest in Surrealism, said New York–based dealer Michael Rosenfeld, who has sold work by Tanning and Sage since the 1990s. As museums and private collections scramble to rebalance their male-heavy rosters, work that expresses female sexual agency and champions gender fluidity is finding a broader collector base. And thanks to careful stewardship by the artists’ longtime galleries and foundations, their markets, already climbing, have further room to run.

Not the “idealized, sexualized woman”

Dorothea Tanning, Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, 1943. © DACS, 2018. Courtesy of Tate.

In their pursuit of subconscious expression, the male Surrealists, such as Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Yves Tanguy, and René Magritte, created imagery that, in its sexual abandon, often objectified women; they chopped off female arms and legs, replaced their faces with genitalia, or, as in the case of Ernst, rendered them headless. Unsurprisingly, André Breton, author of the Surrealist manifesto, had little interest in promoting his female counterparts as equals.

The strongest and most successful Surrealist works by women, according to Sotheby’s specialist Julian Dawes, offered a counterpoint. They are “reflective, contemplative, dealing with womanhood from a searching perspective,” said Dawes, citing the most famous of these women, Frida Kahlo, as an example.

In Kahlo’s works, she was “not this idealized, sexualized woman, but this very natural and stark, graphic and painful” representation of the self. Similarly, American painter Kay Sage’s self-portrait Le passage (1956) shows the artist looking out over a barren, geometric landscape while ominous clouds gather overhead. She is inward-looking; viewers see her only from the back, the impenetrable terrain before her suggesting a neverending cerebral space. (The painting made headlines in 2014 when it sold for $7 million, more than 23 times the previous year’s record for her work, $302,000.)

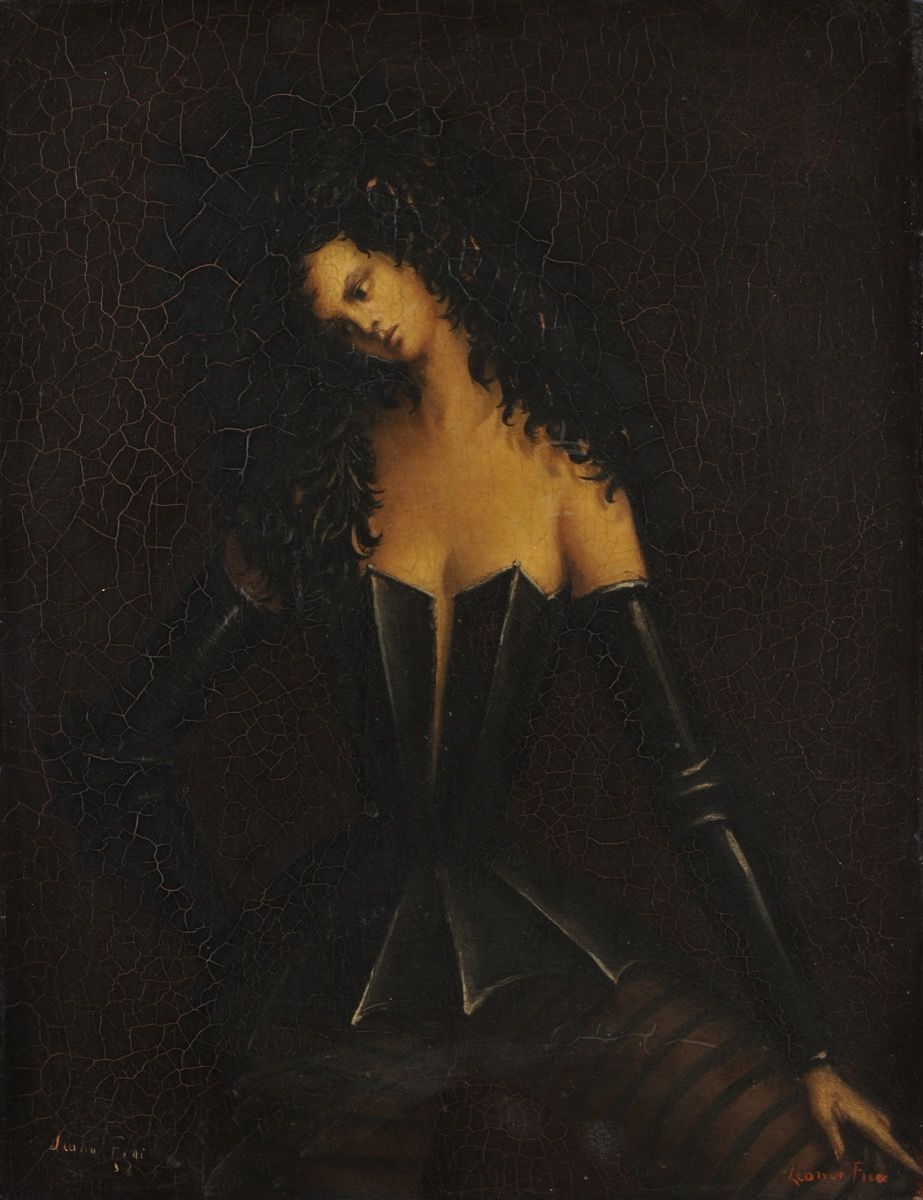

Like their male counterparts, the women of Surrealism, in many cases, worked to liberate their desires through explorations of dreams and mysticism, but to less violent effect. In her painting The Black Room (1939), Leonor Fini—whose work will go on view at New York’s Museum of Sex later this month—painted her close friend Leonora Carrington as a striking, armored figure, seen at the threshold of a dark bed chamber where figures are engaged in ambiguous shadowy activities around a bed. It “suggests ritualized and erotic dream-worlds in which women wield power over ancient ceremonies and mysterious cults of the feminine,” writes Chadwick in Farewell to the Muse.

Kay Sage, Le Passage, 1956. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Leonor Fini, Woman in Armor I (Femme en armure I), c. 1938. Courtesy of Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco, and the Museum of Sex, New York.

They also employed the tools of Surrealism to test the limits of a woman’s place in the world during a period of war and turbulence. Dorothea Tanning, for example, painted fantastical images of women in interior spaces—with wild, gravity-defying hair and wind-swept garments that seem ablaze. She “wreaked havoc on traditional domestic space and objects,” said Alyce Mahon, curator of the Reina Sofia Museum’s upcoming Tanning retrospective (which will travel to the Tate Modern next year) and curatorial advisor for Fini’s upcoming New York exhibition. “She staged a new, modern sense of the feminine as a creative force, which could not be reduced to the traditional roles of muse or mother.”

Fini and Carrington, in particular, interrogated received notions of female identity, a salient theme today amid evolving discourse around gender binaries. Carrington, Chadwick writes, practiced in both her writing and art a “lifelong investigation into hybridity and androgyny as models that challenge sexual difference.” Carrington’s animal avatar was a muscular horse, while Fini’s was a sphinx, which “embodied the way she felt about herself as this inscrutable being that was complicated, a sort of living riddle,” said Dawes.

Around 10 or 15 years ago, even female audiences, Chadwick said, “were sometimes horrified” by the more transgressive examples of their work. Now, women recognize artists like Carrington and Tanning as pioneers who “managed to make something out of Surrealism and themselves that didn’t exist before….They were doing much more than trying to tuck themselves into some art practice.” And it is often women who have championed them, such as Chadwick, Norris, London dealer Alison Jacques (who represents Tanning), and the academics and institutional curators that have given them exhibitions (or are in the process of doing so), among them Ilene Susan Fort, Tere Arcq, Ann Temkin, Alyce Mahon, and Ann Coxon.

GRowing international demand

Dorothea Tanning, The Temptation of St. Anthony, 1945-46. Courtesy of Christie’s.

Dorothea Tanning, The Magic Flower Game, 1941. Courtesy of Sotheby’s

In 2015, Dawes organized a Sotheby’s exhibition of work by female Surrealists, entitled “Cherchez la femme.” Among the collectors discovering the work for the first time, he observed a strong response from female clients. There has also been a slight shift, said Norris, towards a younger base that extends beyond the Surrealism connoisseurs who make up the more traditional buyer pool for these works.

The reputations of the Surrealist women are also growing in other parts of the world. Even Asian collectors, who typically favor more iconic Western artists as they begin to collect, are showing early signs of familiarity with these artists. (Specialists from Sotheby’s and Christie’s report having seen burgeoning interest in the women of Surrealism from Indonesian and Taiwanese buyers.) The dissolving boundary between Western and Latin American art histories has also contributed to their prominence, as artists associated with Mexico—such as Carrington and Varo—gain recognition in other parts of the world, and American artists associated with Surrealism likewise gain traction in Latin America. (This year, Sotheby’s relaxed the boundary between Latin American and Western art histories, bringing the Mexican contingent within the category of Surrealism for the first time, rather than Latin American art.)

Christie’s specialist Virgilio Garza predicts an uptick in institutional acquisitions of works by Carrington across the West. Indeed, Norris is in the midst of negotiations over the sale of works by Carrington and Varo—who was Spanish, but also emigrated to Mexico—with two institutions in the U.S., which she expects to announce by the end of the year.

Earlier this year, the National Gallery of Scotland purchased Carrington’s extraordinary portrait of her former lover Max Ernst, whom she depicts as an androgynous figure in a feathery red costume that extends into a forked tail—suggesting a fusion of Carrington’s “Maremaid” creature and Ernst’s avian alter ego, “Loplop.” The acquisition can be seen as symptomatic of what Garza describes as an institutional effort within the U.K. to “reclaim Leonora Carrington as a European artist, as one of their own.”

Of course, museums have long recognized Kahlo, who has been a global phenomenon for decades, and Meret Oppenheim’s fur-lined teacup was the among the first artworks by a woman to enter MoMA’s collection. But in recent years, they have paid closer attention to the wider spectrum of women associated with Surrealism, in particular to Carrington and Tanning, in part due to their prolificacy and the twists and turns of their artistic practices. Carrington, a British artist who broke with her traditional, privileged upbringing and spent the majority of her life in Mexico, is believed to have made more than 2,000 works. In 2015, the U.K.’s Tate Liverpool organized a retrospective of her work; another followed this year at Mexico City’s Museum of Modern Art, featuring over 200 works.

Tanning, who also had a long, productive life making a diverse range of work that was strikingly ahead of its time—including semi-figurative soft sculptures made two decades ahead of Louise Bourgeois—is better represented in museum collections, a fact that Norris attributes to the work of The Dorothea Tanning Foundation. But she is only receiving her first major retrospective this fall, at Madrid’s Reina Sofía, followed by London’s Tate Modern. (She has yet to receive a retrospective in the United States, though her dream, Norris said, was to show at the Whitney Museum of American Art.)

Tanning has also seen an escalation of interest from private collectors. Her world-record price routinely doubled or tripled in the period between 2009 and 2015, according to auction records and Dawes’s observations. Though that gradient appears to have tapered off—in 2015, Tanning’s The Magic Flower Game (1941) narrowly surpassed $1 million at auction; three years later, in May 2018, the artist’s Temptation of St. Anthony (1945–46) hammered for just shy of $1.2 million, her latest record price—the works sell privately for more. Norris said great works by Tanning and Carrington go for between $1 million and $3 million behind closed doors.

Currently Norris has a waitlist for both Tanning and Varo, but perhaps none go as fast as the works of Sage, which are particularly rare. The American artist, known for her portentous, psychologically loaded landscapes, had a short career and made just a few hundred works. When a painting by her comes into Norris’s hands, she said, it goes within 48 hours.

The scarcity in Sage’s market—much of her work has been in institutional collections for many years—suggests that her sale price will continue to rise as paintings become available. Though Rosenfeld agrees the growing interest in the women of Surrealism has generally been consistent and steady—“not meteoric”—for certain periods of production, it has accelerated more sharply. “There’s a very limited supply of high-quality early paintings by Kay Sage and Dorothea Tanning,” he said, “and there’s a dramatically increasing demand.”

“Room to grow”

Like Sage and Kahlo—the latter of whom has some 300 works or so in existence, most of them in Mexico under national patrimony—Spanish artist Remedios Varo made just a few hundred paintings. Consequently, Norris said, her market is much like Kahlo’s. Though fewer of her works have passed $1 million, “a good work of Varo’s sells for north of $5 million.”

For artists who were more prolific, prices are lower, but dealers and specialists see their relative accessibility as a boon to developing interest in a market that until 10 or 15 years ago was niche. When Dawes put together “Cherchez la femme” in 2015, there were “really undeniable A-plus pictures available in some way, shape, or form for all of the female Surrealists,” which is important, he said, in terms of “making people feel energized and excited to participate in that market.”

Today, organizing such an exhibition might be harder to pull off. But while the great works of the male Surrealists are largely locked away in museum collections, the strongest work of the female Surrealists is relatively accessible both in price point and availability. “We have access to these absolutely extraordinary examples of some of the best work by the female members of the Surrealist movement in a way that we don’t at all have for the male counterparts,” said Dawes.

He pointed to Magritte, who did thousands of repetitive gouaches. “A gouache from the ’60s that’s fine might sell for $2 million,” he said, “whereas the greatest Tanning ever—which, frankly, two of them were just sold in the last two years—barely broke $1 million. That still has room to grow.”

Leonor Fini, The Blind Ones (Les Aveugles), 1968. Courtesy of Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco and the Museum of Sex, New York.

Since collectors favor earlier works from the 1930s and ’40s—the recognizably Surrealist works that were made during the movement’s zenith—there is also considerably more room for growth when it comes to later works made by these artists. In the case of Tanning, for instance, collectors hanker after the more figural work of the 1940s, while her more abstract pieces made after the late ’50s—complex, swirling atmospheres of undulating form and color, described by scholar Catriona McAra as “kaleidoscopic”—go relatively overlooked.

Yet some believe these late pieces are her most virtuosic. Tate curator Ann Coxon, who is organizing the institution’s iteration of the Tanning retrospective, sees these paintings as the artist stepping away from Surrealism as we know it and finding her own voice. “There is a confidence about those paintings, which [underscores] the fact that she doesn’t really care how she’s categorized anymore,” Coxon said. She is “making her own imagery.” For Norris, who will take a selection of Tanning’s kaleidoscopic paintings (priced at $30,000 to $750,000) to Expo Chicago later in September, they are her most visionary pieces. “Those to me are just the most painterly, magnificent works,” she said.

While buyers will drop millions on a Dalí oil from the 1970s, the late works of the women of Surrealism are valued at a fraction of the price. “There’s a massive robust global market for the late works of [the male Surrealists] because their names are so iconic,” said Dawes. “That has not come to bear yet for the female artists.”

He is confident that the time will come when the lesser-known women of Surrealism, who extend to many others not here mentioned—like Lee Miller, Valentine Penrose, Toyen, Bridget Tichenor, and Gertrude Abercrombie (whose current exhibition at New York’s Karma, her first New York show in decades, received an enthusiastic review in the New York Times)—reach “a place of parity with the male Surrealists.”

Tanning, according to Norris, knew her time was coming. Carrington too, perhaps. To her former lover Max Ernst, she was, as Chadwick writes, “a surrealist woman-child, destined to inspire [man] through her youth, her beauty and her innocence.” To her friend Leonor Fini—who refused to formally join the chauvinist Breton’s movement—Carrington was “never a surrealist, but a true revolutionary.”