The Romance and Heartbreak of Writing in a Language Not Your Own,

The Romance and Heartbreak of Writing in a Language Not Your Own

By PARUL SEHGALJUNE 2, 2017

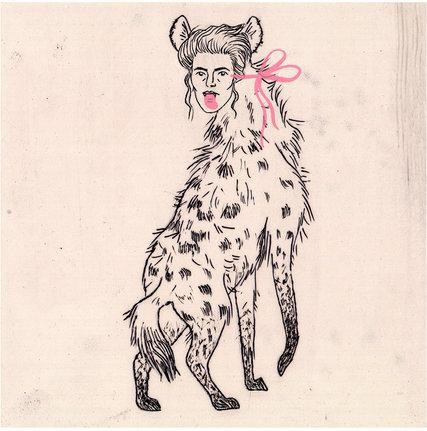

CreditMaëlle Doliveux

As a child, Leonora Carrington — painter, fabulist, incorrigible eccentric — developed the disconcerting ability to write backward with her left hand while writing forward with her right. This trick did not go over well with English convent school nuns. Between the world wars, Carrington was thrown out of one school after another for persistently odd behavior. When she came of age, she fled England — and her family’s fortune — for France and the Surrealists, for a life crammed with incident and adventure, occasional poverty and steady productivity. She died in Mexico City in 2011, at the age of 94, leavingbehind paintings and stories full of strange, spectral charm, in which women undress down to their skeletons and a sociable hyena might venture out to a debutante ball, wearing the face of a murdered maid.

This year marks the centennial of her birth, and three of her books have just been reissued: THE COMPLETE STORIES (Dorothy, paper, $16); DOWN BELOW (New York Review Books, paper, $14), a memoir of her months in a mental institution in Spain; and THE MILK OF DREAMS (New York Review Children’s Collection, $15.95), her fables for children. Carrington never stopped writing with both hands; she is always telling two stories at once. “Leonora told me that every piece of writing she ever did was autobiographical,” her biographer Joanna Moorhead recalled. In her short story “The Oval Lady,” for example, the teenage Lucretia, who loathes her father (“I’d like to starve myself to death just to annoy him. What a pig”), is violently subdued by her nanny, who jams a bit between her teeth and climbs on top of the girl, clinging to her back while Lucretia wrecks the room. It’s a loose-limbed little exercise — Carrington is just flexing her imagination. But it is as truthful as it is playful; here is her childhood in miniature: the lifelong weirdness with food, the threat of institutionalization, the domineering father and his proxy, the nanny. (Carrington’s own nanny was dispatched on a warship to rescue her from an asylum in Spain to send her to another in South America.) Behind the special effects frequently lurks a fearful or desperate moment from her own life. As the most famous Carrington story goes, she once cut off the hair of a much loathed houseguest in the middle of the night and served it to him in an omelet in the morning. This is the best description of what it feels like to read her work: In the middle of the fluffy fairy tale, something bristles, something unpleasantly familiar, something human and frightening.

Carrington is also a member of a select group of writers — exophonic writers, they’re now called — who work outside their mother tongues. Her memoir, “Down Below,” has perhaps the most unusual translation story I’ve heard. After her first husband, the Surrealist painter Max Ernst, was sent to a concentration camp, Carrington suffered a nervous breakdown and began tobelieve that by purging she could purify the world. She was sent to an asylum in which treatment amounted to a form of torture: She had artificial abscesses induced in her thighs to keep her from walking and was administered drugs that simulated electroshock therapy. She first wrote of these experiences in English in 1942 and promptly lost the manuscript. Later, she told the story to friends in Mexico City, one of whom jotted it down in French. It was then translated back into English to be excerpted in a Surrealist journal in 1944. The blurriness in tone is partly intentional and partly, one suspects, a consequence of being much handled. Many of her pointed short stories were also written in her rudimentary French or Spanish. Her tentativeness with the languages accounts for the “delinquent pleasure of her voice,” Marina Warner writes in a new introduction to “Down Below.” “Unfamiliarity does not cramp her style; rather it sharpens the flavor of ingenuous knowingness that so enthralled the Surrealists.”

Sounds appealing, no? I tried my own hand at it, and first wrote the previous paragraph (slowly and unhappily) in Hindi, a language I’ve spoken all my life but rarely written in, and then translated it (slowly, with much cheating) into English. It was an unpleasant, embarrassing exercise, like being blindfolded and shoved into a strange room. Every direction I turned brought me into thudding collision with my limits. Writing can often feel like this — but rarely to such a painful degree. How puny is my vocabulary in Hindi, I realized, how muddled my thinking, how equivocal and hesitant I become; it’s as if something of myself as a child has been preserved there. To move back into English was a relief. Why would Carrington choose to hamstring herself like this? Why would anyone?

There are as many reasons as there are kinds of writers. There is the exophonic writer who is the product of historical trauma and dislocation — Nabokov in exile, for example: “My private tragedy, which cannot, indeed should not, be anybody’s concern, is that I had to abandon my naturallanguage, my natural idiom.” It can be a way to find a larger audience — think of Joseph Conrad — or it might allow the writer to pursue a natural affinity for another language. The Japanese writer Yuko Otomo, who writes primarily in English, delights in its democratic impulses: “I love the fact that English does not have hierarchical elements that Japanese weighs on and is very clear-cut. I am elated to address a professor and a dog with the same pronoun ‘you.’” For some writers it allows an exciting rebirth. “Dissecting my linguistic metamorphosis, I realize that I’m trying to get away from something, to free myself,” Jhumpa Lahiri has written of her decision to read and write exclusively in Italian, which has allowed her to become “a tougher, freer writer, who, taking root again, grows in a different way.” For others the draw is less an interest in shaping a future than in decisively purging themselves of the past. Emil Cioran: “When I changed my language, I annihilated my past. I changed my entire life.” Yiyun Li has written that she adopted English in her 20s with a kind of absoluteness that was tantamount to suicide.

The opposite ambition spurred on Carrington. Other languages seem to afford her more life, more lives. She relished feeling ungainly and unsure. Far from feeling impoverished by a smaller vocabulary she felt liberated. “The fact that I had to speak a language I was not acquainted with was crucial,” she wrote of her time in Spain. “I was not hindered by a preconceived idea of the words, and I but half understood their modern meaning. This made it possible for me to invest the most ordinary phrases with a hermetic significance.” This sentiment recalls Samuel Beckett, who also appreciated the “weakening” effect of working in a foreign tongue. He adopted French, he said, to be “mal armé,” poorly defended. He’s having a bit of fun here — “mal armé” is probably a play on Mallarmé — but he was famously intent on shucking off his style. “It is indeed becoming more and more difficult, even senseless, for me to write an official English,” he wrote in a letter in 1937. “More and more my own language appears to me like a veil that must be torn apart in order to get at the things (or the Nothingness) behind it. Grammarand Style. To me they seem to have become as irrelevant as a Victorian bathing suit or the imperturbability of a true gentleman. A mask.”

Here Carrington happily parts ways. She was a writer who insisted on more veils, more masks. It’s said she loved the Egyptian room at the Met, that the sight of all those tightly wrapped mummies was deeply reassuring to her, that she loved basement apartments and living below the ground. Every language she learned seemed to offer a new place to conceal herself, to hide in plain sight — but never out of cowardice. In her elaborately surreal English, in her simple French and Spanish, she kept revisiting her places of fear, almost compulsively retelling her story. “The more strongly I smelled the lion,” she ends one story, “the more loudly I sang.”

Parul Sehgal is senior editor of the Book Review.