Julio César Morales “Review: Emotional Violence

Review

Emotional Violence

December 3, 2015

The title of Julio César Morales’ exhibition of new works at Gallery Wendi Norris notifies the viewer that this work will not be light or, at its essence, easy—and this is the case, though Morales’ difficult subjects are deftly handled, able to be contemplated and digested in all their anguish.

The work in Emotional Violence continues Morales’ ongoing conceptual exploration of such weighty and all-too-current topics as illegal border crossing, drug smuggling, human trafficking, displaced peoples, and informal economies. As has long been his practice, Morales looks to the media and documentary photography for source material to inspire the ceramic, video, and flat works included in the exhibition.

A strength of Morales’ work is its subtlety. He uses humor, color, and editing or abstraction to provide an entry point to challenging realities, giving viewers a way to sit with and contemplate what they may usually feel the urge to walk away from. His regular use of repetition allows these subtle but powerful messages to sink in.

Courtesy of Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

For instance, he’s made several lifelike replicas of foil-wrapped burritos out of ceramic in theWetback Burrito 1–6 series (2015); on the bottom of each the artist has written “wetback,” which is certain toraise questions. Given the writing on the piece as well as the heavier issues hinted at in the surrounding work and the works’ title, we can surmise that there’s more to the story. And, yes, these delicious-looking packages represent the burrito thrown by an unidentified person into a camp of people in Phoenix, Arizona, who were protesting the holding of over 40,000 people in U.S. detention centers. That burrito had written on it “LEARN ENGLISH WETBACK WETBACK GO BACK TO MEXICO”; the fact that Morales’ work features only one, albeit offensive, word could likely be attributed to his desire to not be heavy handed. (It could also be seen as a signature—Morales is Mexican American—in the artist’s cooptation of this racial slur, standing in solidarity with the protesters.)

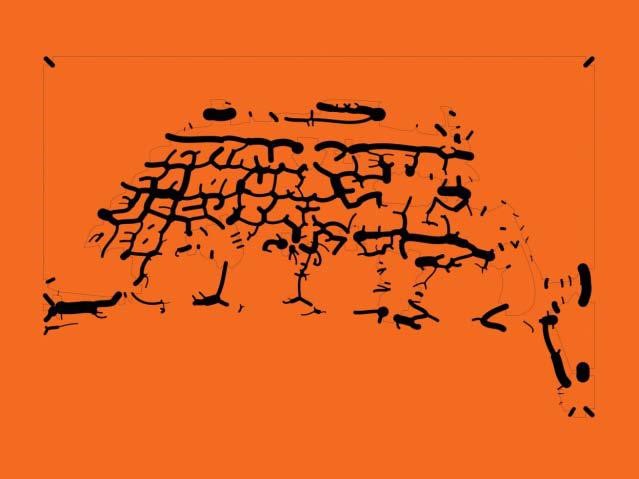

Morales’ editing becomes more extreme the more gut-wrenching and grotesque his subjects are. This serves to both strengthen the narrative—it’s not cluttered by excess, and it renders the viewer curious about what the total narrative is—and protect the viewer, as being confronted too directly by such atrocities could quickly render one numb. There’s always more going on than Morales immediately lets on. This could also alert us to be wary that the seemingly prettier and more obscure the work, the more awful the reality. By example, there are three works that feature a bright orange background on which is what almost looks like an X-ray image in black, all lines and unidentifiable organic forms; any image is unclear. They are eye-catching, with a Pop aesthetic. Think Andy Warhol’s Electric Chair, but more recondite.

The origins of these works are photographs of people beheaded by the drug cartels south of the U.S. border. Morales’ referencing of the Pop genre, which is associated with advertising and repetition, further serves to add to the macabre message; this is a form of communication (sick “advertising”) by the drug lords, and it happens repeatedly.

Highly abstracted, too, is the short video (3.33 minutes) Boy in Suitcase (2015); it’s as poetic as it is powerful. Most of the piece shows highly pixelated and fluidly moving soft colors accompanied by soothing but almost eerie music; it feels like a dream or drug trip. But given the overriding message of the show, we know we are headed for something more nightmarish, a bad trip. As the video ends, an image—the only recognizable one shown in the piece—begins to form, and finally we can see an X-rayed roller-suitcase with a person folded up inside, the image pink-red against a turquoise background (transporting people in such tortuous ways has been a focus for Morales). The pixelated imagery depicts a stylized interpretation of what the boy in the bag may have seen during his journey, as it is believed that the zipper had been slightly open, allowing him a small window to view the outside.

Graciously, Morales does provide us a moment or two of comic relief in the show with hisNarco Headlines series, which features black headline-style phrases on white paper, framed (all the same size: 22 by 30 inches) and hung one next to the other. Each one describes an inventive method of drug transportation: “Ketamine Holy Water,” “4.5 Lbs. of Cocaine Found in Dreadlocks,” “Mr. Potato Head Full of Ecstasy,” and so on. One can’t help but chuckle at the chosen verbiage, but also note the audacity of traffickers in preying on innocence. The larger, more serious message is clear: These ruthless drug lords will cross any moral boundary, capitalize on all imaginable wrong assumptions, to move product.

Using photos in a state closest to the original is the installation Failure Loop (2015), a series of framed 8.5-by- 11-inch images that run down the wall and continue along the floor; imagine a length of film reel. Some of the images show what has been addressed elsewhere in the show, for example the woman whose dreadlocks held the “4.5 pounds of cocaine”; others speak to the various themes the show is focused on, such as the blight of displaced people. A shot of the drowned Syrian boy who was much covered in the media is among the pictures.

In sequential, repeated order, the images are first red toned, then green toned, then blue toned, thus referencing RGB, the system used to represent color on a computer screen. In combination with the title word “loop,” thoughts of repetition and widespread distribution readily come to mind; adding to this the title word “failure,” the implication is that the ample spread of this information is not changing things (or at least not enough). By presenting them all together, Morales alters the single-incident reporting found in the press, relaying a stronger message of rampant human cruelty, current and global.

Morales highlights that which we’re continually exposed to but seem not to truly see. By reformatting the message, he provides us with a way to absorb the unfathomable, face-deep but true ugliness. And so taken in, these images and the darkness they represent, sublime and strong, remain with you, visually and viscerally.