Rohini Devasher: Visions of the Sun

Installation view, One Hundred Thousand Suns, 4-channel film, 25 minutes

Gabrielle Selz

Febraury 7, 2024

Rohini Devasher loves the sky. She joined the Amateur Astronomers Association while enrolled in the College of Art in New Delhi in 1997 and has been mesmerized ever since. One Hundred Thousand Suns, the artist’s first US solo exhibition debuting at the Minnesota Street Project Foundation (MSPF) and Gallery Wendi Norris, is a realization of her twin passions for art and science. In each discipline, Devasher found herself confronted by similar questions. How do we observe? What do we observe? How does the act of observation change the viewer and the subject?

The focal point of the MSPF exhibition is a 20-minute four-channel film, One Hundred Thousand Suns (which is showing simultaneously at the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum in Mumbai, India, in collaboration with Project 88, and at Museum Catharijneconvent in Utrecht, Netherlands). The project, launched 12 years ago, explores distinct dimensions of the Sun (material, ephemeral, geographic) and centers around the history, instruments and astronomers at the Kodaikanal Solar Observatory in southern India, where four generations of one family have been observing the night sky since 1901. The film follows the evolution of solar observation, from early hand-drawn images of the solar disk to glass-plate astrophotography to images of the Sun during a solar eclipse caught in the beam of Kodaikanal’s 60-meter tunnel telescope. While the Sun is the most visible object in the sky, it’s also the most difficult to behold with the naked eye; yet here we see it observed and recorded with various methods and media.

Installation view, One Hundred Thousand Suns, 4-channel film, 25 minutes

In some of the most compelling segments of the film, Devasher’s footage of a solar eclipse is accompanied and enhanced by interviews with eclipse chasers: people who devote their lives to standing in the shadow of the moon. During a total solar eclipse of the sun, the moon passes between the Sun and the Earth, enveloping the Earth in a darkness so complete one astronomer remarked, “I’ve never seen such intensity in black.” Here, we see it, too: in the elegant choreography between three elements in space, when the moon’s shadow slides over the sun and shuts out the light like an eyelid closing. “It was the moment in my life when I became aware that I was standing on a body in space,” Devasher said of her first glimpse of a total eclipse, an experience so wonderous, she spent more than two decades pursuing it.

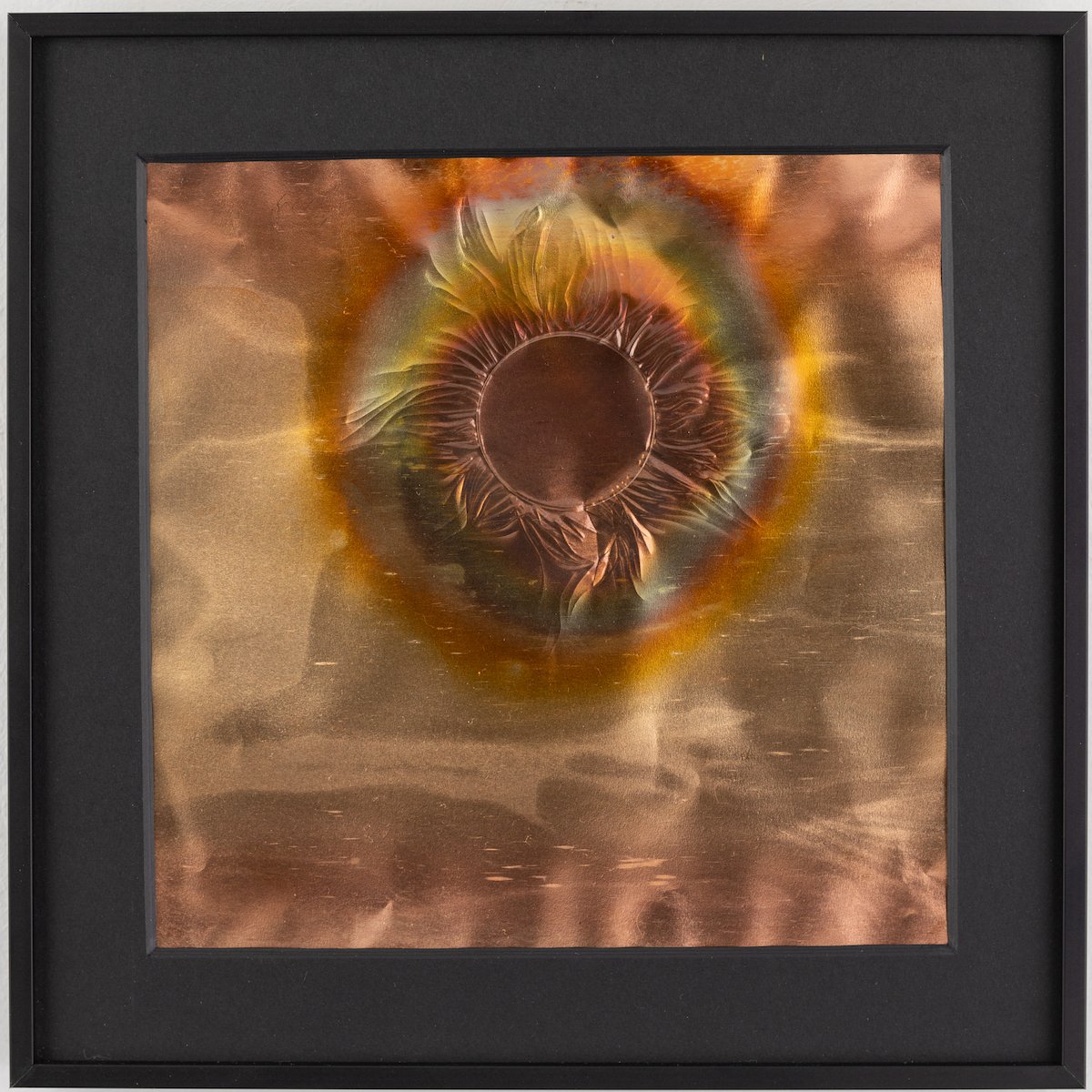

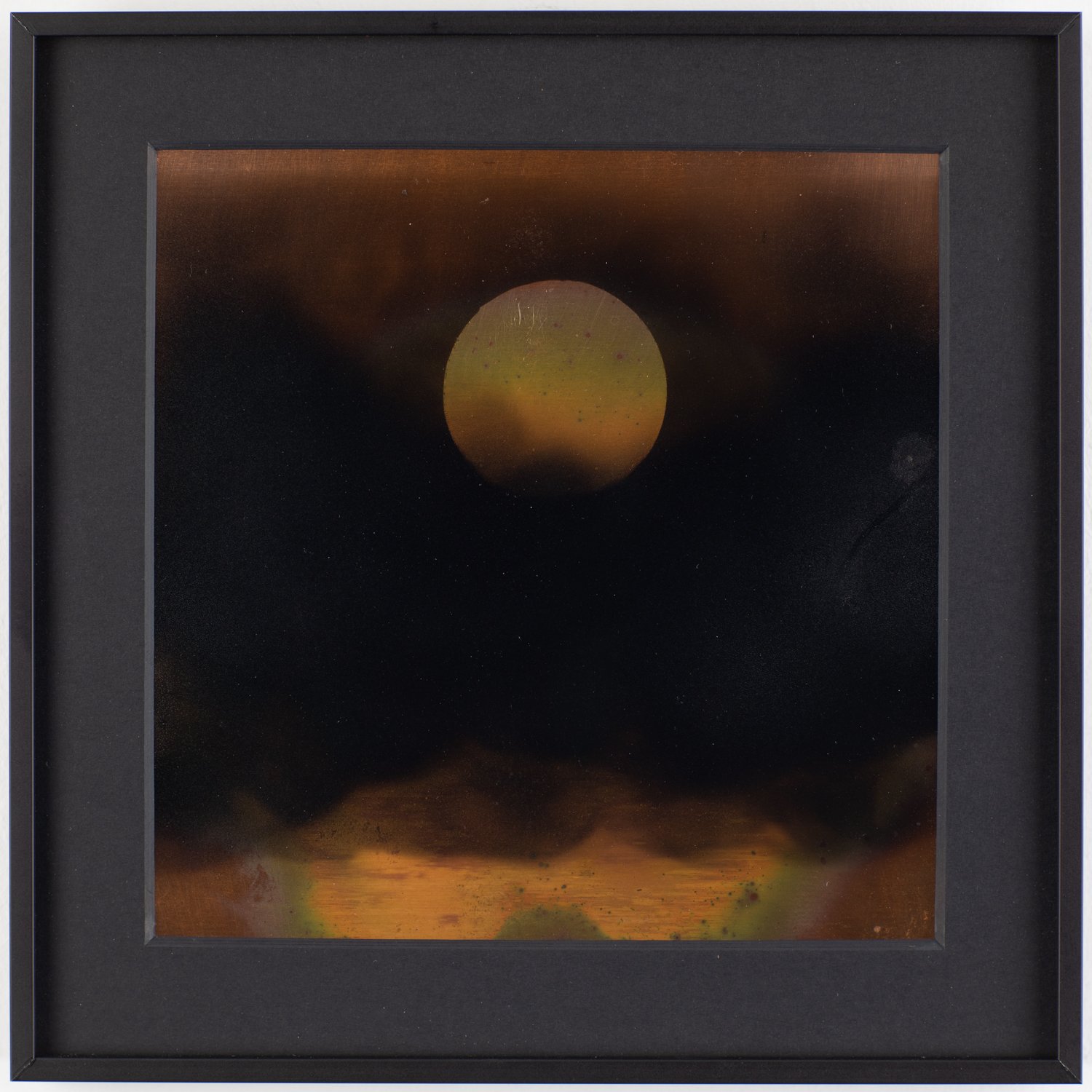

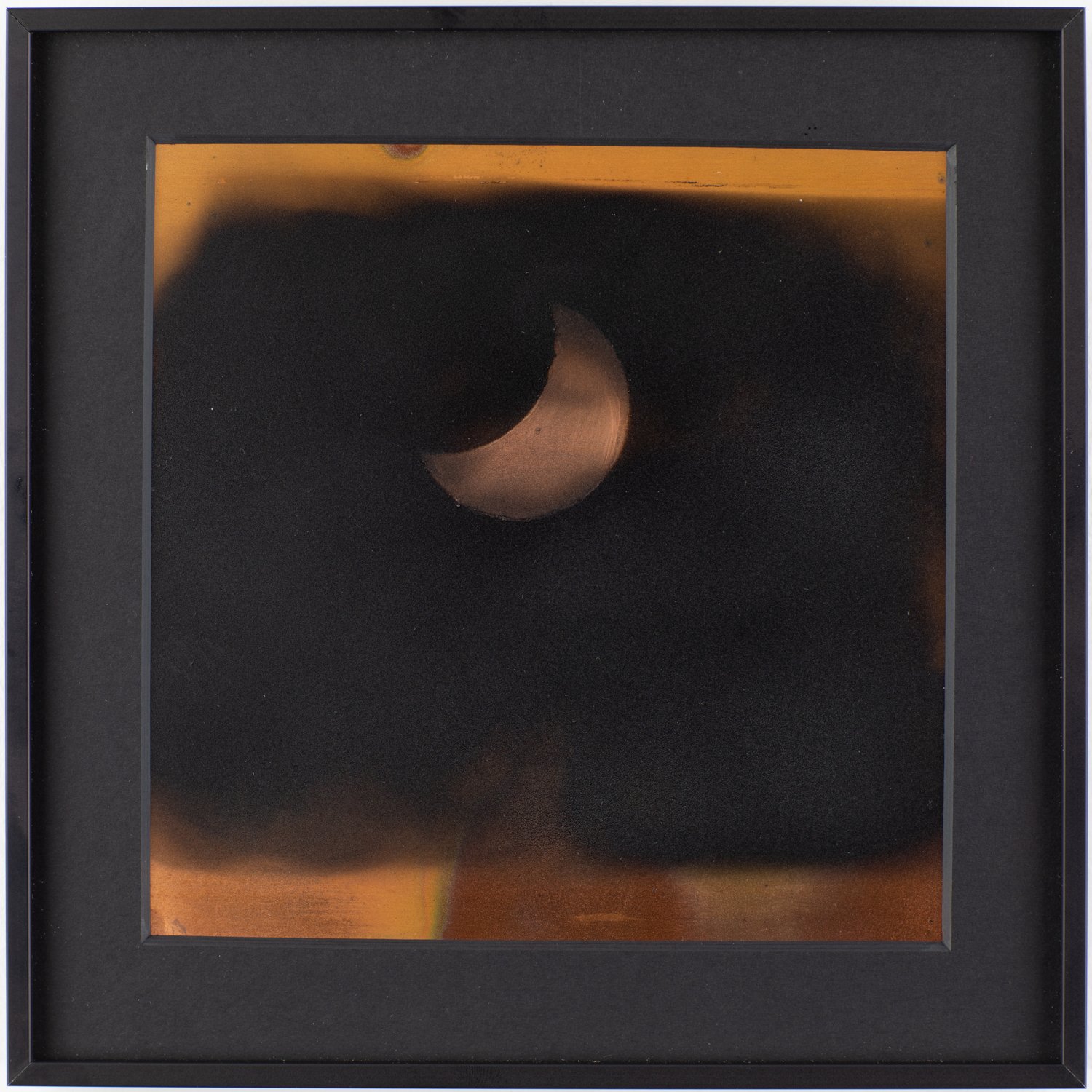

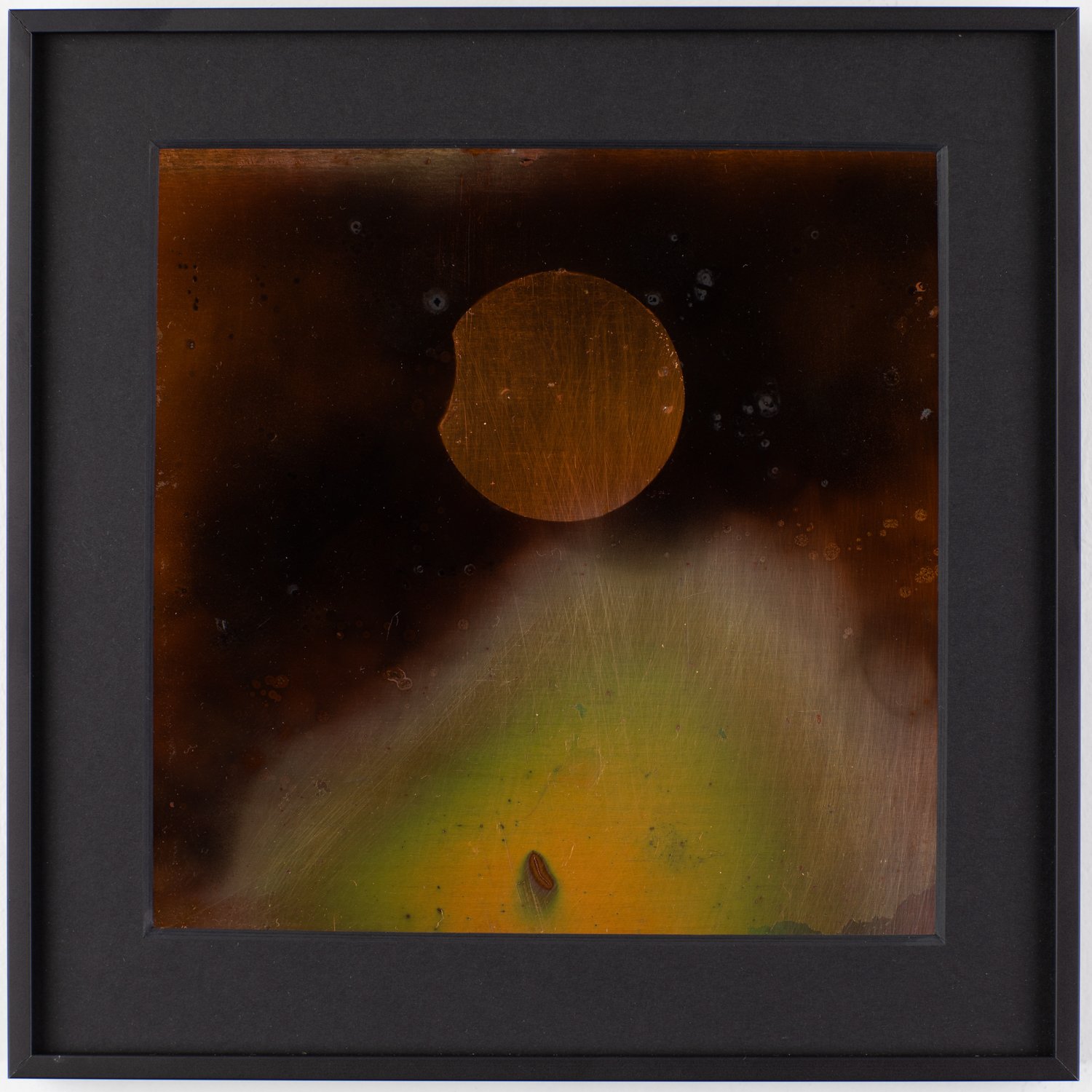

Installation view: Latent Fields, 2024

The film is accompanied by the site-specific work Latent Fields, an immersive installation designed for the towering, vaulted (and chilly) space at the MSPF. It features a series of massive, digitally printed silk panels hung from the ceiling, displaying images that move from the subatomic to the atmospheric and from the macro-scale of the thin ring of the Sun’s corona to the micro-scale of the human eye, all of which draw our attention to the act of seeing. The artist imbues the panels with a lustrous sheen by printing her drawings of celestial bodies and photos of nanoparticles first onto copper sheets before rephotographing and reprinting them onto silk. The resulting comingling of distortions produces strange, improbable amalgamations in which patterns emerge and push against one another but are held in place on the luminous silk cloth as part of an interconnected system.

While the panels of Latent Fields are stunning in their grand, theatrical presence, allowing light to penetrate them and air to move them, Dashner’s Shadow Portraits and Sol Drawings are discrete and stationary. For these works, she uses copper for its link to the sun, believed to be the source of it and other heavy metals on Earth, forged in stars half a billion years ago. Three of the larger Portraits are displayed at MSPF; the remainder, more than 40, are arrayed like a constellation across the walls of Gallery Wendi Norris in an exhibition titled Sol Drawings. In these, Devasher utilized fumage, a technique of drawing with smoke, popularized by the surrealist Wolfgang Paalen, who used it to portray the subconscious in paintings. Devasher uses it for an entirely different purpose. Employing her kitchen stove top and candle smoke, she created patterns ranging from flares and spots to plumages and flower-like growths that shift between blue-purple hues and golden copper. Like light, smoke can be blinding and obscuring, but in these images it illustrates and elucidates, becoming a tool for observation and interpretation. Other works, like Skywatch, Devasher created on etching paper. Rather than serve as a substrate, copper in these pieces represents the sun’s movement as the artist tracked it for a month in different cycles across the sky.

The universe is said to be a silent and colorless place—just waves and particles. It is we who construct the colors and sounds by assigning values. It is we who, through various instruments, see light sometimes as particles and at other times as waves. Devasher reminds us how strange and magical this act of observation can be. Light, it turns out, is whatever we observe it to be. Her art shows us that humans are not recording instruments but revelatory ones. As observers, we construct the pictures through interpretation and bring the world into being. We create what we see.