The Meaning of the Moon, From the Incas to the Space Race

The Meaning of the Moon, From the Incas to the Space Race

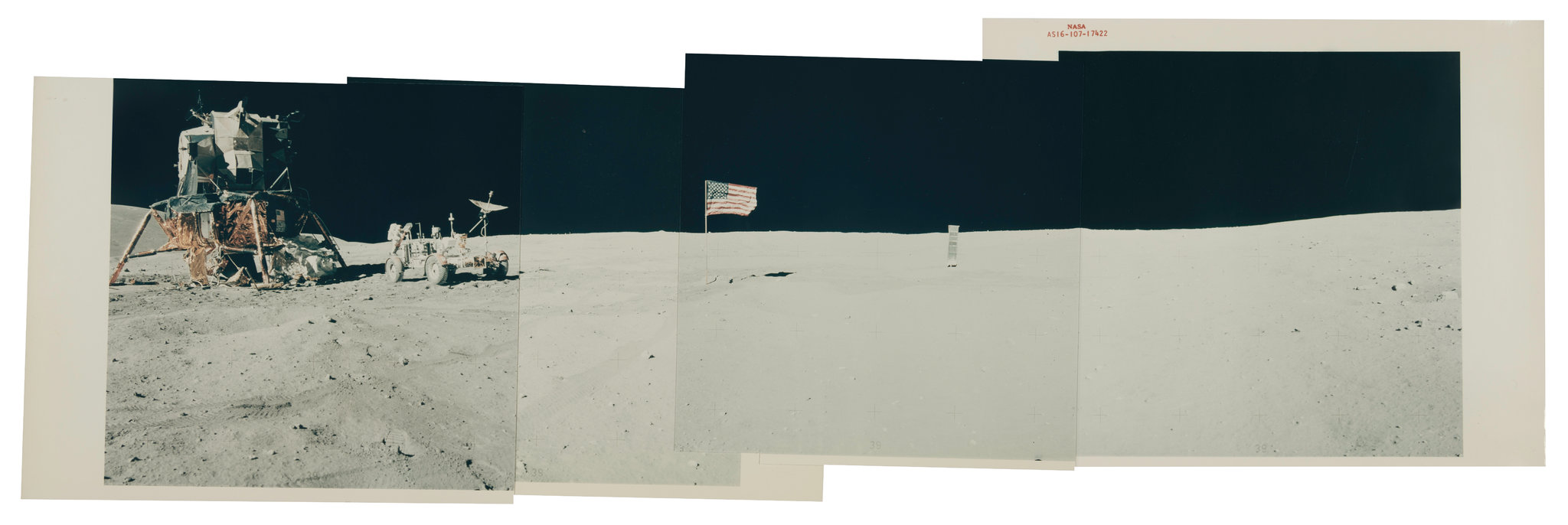

A panoramic view of the Descartes landing site from the Apollo 16 mission. The Louisiana Museum in Denmark’s new exhibition “The Moon: From Inner Worlds to Outer Space” examines humanity’s fascination with the moon over hundreds of years.CreditCreditNASA and Collection Victor Martin-Malburet

By Andrew Dickson

Sept. 12, 2018

COPENHAGEN — Outside Denmark’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art on a recent late-summer morning, a few sunstruck visitors were sprawling on the turf of the sculpture garden, between monumental outdoor works by Alexander Calder and Richard Serra. Beyond them, facing east toward Sweden, the waters of the Oresund strait were a serene blue, lightly scalloped with wind. The scent of freshly cut grass was in the air.

Inside, however, it was another world. Under chilly artificial light, art handlers were hoisting large prints onto white gallery walls. One was an abstract, composition of fuzzy shadows and white splotches, like a Jackson Pollock viewed under a microscope: in fact, a recent NASA image of the moon’s surface. Nearby, another work was already up — a reproduction of a childlike engraving from 1793 by the English artist William Blake. It depicts a tiny figure climbing a ladder that reaches all the way to the moon. Blake’s caption beneath the picture reads, “I want! I want!”

As the Louisiana’s new exhibition, “The Moon: From Inner Worlds to Outer Space,” reveals, humans have wanted the moon for most of our history — wanted to understand it, capture it, land on it, own it. The show, which runs through Jan. 20, is notionally inspired by the upcoming 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission, yet its focus isn’t solely on science or spacecraft, but on art and literature, too. Indeed, the suggestion is that we cannot hope to comprehend the moon if we try to pin it down to one thing. Every time we look up, it’s different.

The moon as photographed by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera.Credit NASA

“The moon has always been an object of fascination,” the show’s lead curator, Marie Laurberg, said, picking her way between crates strewn over the gallery floor. “We’ll never be done with it.”

She conceded that this was unusual territory for the Louisiana, a museum more accustomed to showing work by contemporary and modern artists — but that was very much the point. “We wanted to make a dialogue between art and science,” she said, adding: “We traveled there imaginatively long before we were physically able to.”

That duality dominates the show, which contains over 200 objects. After strolling past a player piano performing a version of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata,” visitors can sample that light, even during the day: A solitary bulb has been adjusted by the Scottish artist Katie Paterson to recreate the specific frequency of moonlight and suspended in a darkened room.

Robert Rauschenberg’s “Sky Garden,” from the 1969-70 series “Stoned Moon.” Credit Robert Rauschenberg Foundation and Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

One artist who has been especially fascinated by the conversation between real-life exploration of the cosmos and journeys of the imagination is Laurie Anderson; a new work commissioned from her is one of the show’s big selling points. Ms. Anderson became NASA’s first artist in residence in 2004, and has referenced space frequently in her music and performance.

Working with the Taiwanese new-media artist Hsin-Chien Huang, Ms. Anderson has cocreated a virtual reality piece that enables participants to traverse a moonscape of her devising. The installation will sit alongside other responses to the space race, both artistic and astronomical: Also on display will be a glove worn by an astronaut, Eugene A. Cernan, during the Apollo 17 mission, still daubed with moon dust, and some modish designs for 1960s Soviet spacecraft.

Ms. Anderson said in a telephone interview that she wanted to preserve the piece’s surprises (specialists were still working out if some aspects of the story she wanted to tell were technically feasible), but hinted that participants would be able to explore a version of the moon that had been turned into a nuclear waste dump, a plan once floated by NASA. Another section will offer what she described as an “out-of-body” experience.

Romantic painters like Joseph Wright of Derby were drawn to the quality of moonlight in nocturnal landscape paintings. His “Lake with Castle on a Hill” dates from 1787. Credit Saint Louis Art Museum

“It’s not meant to be like moonwalking or realistic or one-sixth gravity or anything,” she said. “It’s much wackier than that.”

But then, responses to the moon have always had a touch of fantasy. For ancient civilizations, it appeared as everything from a fertility goddess married to the sun (an Inca origin myth) to something that drove women mad, or transformed men into werewolves (European folklore).

Nineteenth-century Romantic artists such as the English painter Joseph Wright of Derby and the German Caspar David Friedrich painted landscapes by moonlight: Lakes look like pools of mercury, ruins are cast in eerie shadow. That tradition has been continued by the British artist Darren Almond, whose recent “Fullmoon” photographs, some of which are exhibited, involved long exposures in remote locations, the only places free enough of light pollution to capture unfiltered moonlight.

The British artist Darren Almond’s “Fullmoon” series was made with long nighttime exposures in remote locations — the only places free enough of light pollution to capture unfiltered moonlight. Credit Darren Almond/White Cube

“The moon’s face is a storyboard: It means so many things,” Anthony F. Aveni, who teaches astronomy and anthropology at Colgate University, said in an interview. “It’s so close, but it’s so alien, so other.”

“Just as it reflects the sun’s light, so it reflects what we on Earth want,” said Ms. Laurberg. “And every age wants a slightly different thing.”

Much moon iconography, particularly from the space race years, is heroic — men and their rockets, depicted by artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Richard Hamilton. In the show, though, this sense of boyish adventure is nicely undercut by the German sculptor Isa Genzken, one of whose “Wind” sculptures from 2009 resembles an American flag featuring an image of astronauts, but is made out of torn scraps of fabric and decorated, surreally, with strips of bacon.

A rare hand-colored version of Georges Méliès’s 1902 silent movie “A Trip to the Moon” is projected onto a wall of the museum. Credit Lobster Films — Groupama Gan Foundation — Technicolor Foundation

Ms. Anderson pointed out that the 12 astronauts who landed during the Apollo program were pilots and scientists, and hardly trained to respond the experience in more philosophical or creative terms. “They just said, ‘Gee, the Earth’s so far away.’ They left the rest of us thinking how incredibly awe-struck they must have been; they couldn’t even define it.”

Perhaps artists are better at imagining the unimaginable, she added. “Every time I look at the moon, I see the beauty of something that reflects rather than generates.”

In an upstairs gallery, a technician was carefully unwrapping an exhibit lent by the University of Copenhagen: A chunk of lunar meteorite, not much larger than a baseball, which detached from the moon’s orbit and fell to earth some time in the last few million years.

Jagged and black, scarred and strangely sinister, it was a reminder that the moon is barren, lifeless and brutally inhospitable. We have spent lifetimes projecting fantasies on to its surface, populating it with everything from the kindly rabbit of Chinese mythology to the insectlike lunar dwellers of Georges Méliès’s 1902 film “A Voyage to the Moon.” But the moon itself seems coldly indifferent to our interest.

Strikingly, too, the meteorite had an intensity that made the art works elsewhere in the room seem wan and pallid. An alien and unsettling object, literally otherworldly, it captured something that many human representations fail to. Even in an art gallery, the real moon somehow stole the show.

The Moon: From Inner Worlds to Outer Space

Through Jan. 20 at the Louisiana Museum, Humlebaek, Denmark; lousiana.dk.